|

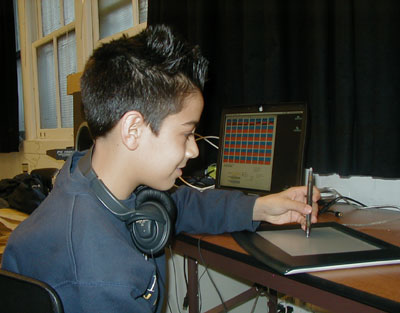

Wind Symphony: PRESENTATION OF THE CONCEPT AND OF THE REALIZATION PROCESS Thanassis Rikakis The following paragraphs give a brief, illustrated, summary of the concept and realization processes of the first stage of the project (a summary of the work done in the first five sessions). Children have strong, implicit, exposure -based, knowledge of the sound environments they encounter in everyday life. This project takes advantage of this implicit knowledge to familiarize children with general issues of sound structures and specific issues of digital sound. For the first stage of this project we decided to concentrate on wind sounds. We asked children to create a wide range of wind sounds and wind based sound environments through the use of digitally filtered white noise. We wanted children to experience the physical forces that are involved in the production of each sound. We therefore chose to work with an external controller that would facilitate this kind of experience. Each child worked with a Wacom tablet attached to a computer:

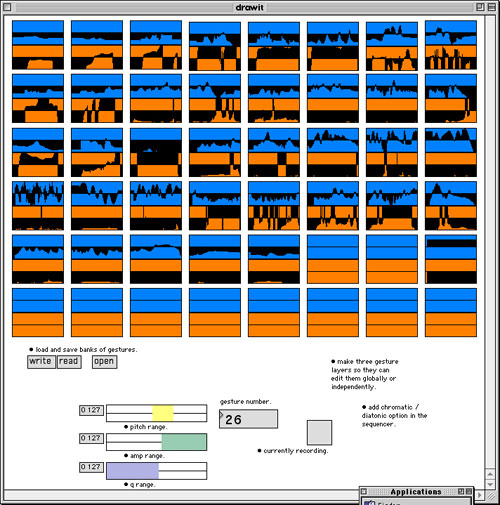

All parameters of the digital filters being used were mapped to specific motion elements of the hand controlling the Wacom tablet.. Thus speed and pressure of motion were mapped into amplitude. Angle (tilt) of motion was mapped into filter width. The vertical (height) dimension of motion was mapped into pitch. The horizontal dimension of motion was mapped into sound spatialization. The mapping decisions aimed to help the children realise the physical forces and interactions that are involved in the production of a sound in general and in the sound of wind in specific. The choice of controller and the mapping choices enhanced for the children the correlation of motion/energy to sound. We started our first session by asking the children to create all types of wind sounds using their voice: from light wind gusts, to howling wind during a storm, to songs played by blowing wind into a bottle; from shot burst of wind to swiping wind gestures. We asked the children to pay close attention to what they had to physically do to create these sounds. We were thus able to connect most elements of the produced sound (volume, duration, pitch, colour etc) to their physical correlates. At that point we asked the children to recreate the sounds the made with their voices by using the Wacom tablet (that was driving digital filtering of white noise). All the children had to do was to recreate through their hand motions/gestures the physical forces/interactions involved in the creation of the sounds. The mapping of gesture parameters to sound creation would take care of the rest. Once the children were happy with a digital wind sound they had created they could save that sound. When the children were saving a sound what was actually being saved were the physical parameters of the gesture that created the sound (height, pressure, speed and tilt over time). Those parameters were mapped into two-dimensional arrays. The schematics (graphic representations) of those arrays became the images shown to the kids for each saved gesture/sound. Thus the children could associate each saved sound with a graph of the evolution of its key generating parameters over time. The children created and saved many wind sounds. At the end of the first session each child had put together a library of single wind sounds. The children could play back any of the saved gestures/sounds of the library by simply pushing on the image (graphic representation) of the sound.

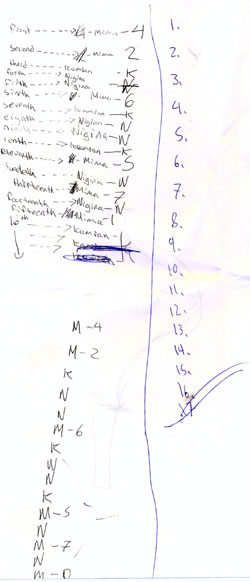

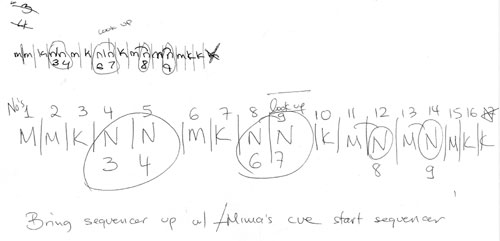

Nigina's library of sounds At that point we started discussing the process involved in creating a longer phrase out of the single wind sounds that the kids had saved. We asked the children to use the saved wind sounds for the creation of a wind conversation. One child was to start the conversation by playing back one of their sounds. One of the other two children would then choose, from their own library of sounds, the wind sound that could best follow the sound just heard. Once the second sound of the conversation was chosen, any of the three children could add a third sound that would be followed by the addition of a fourth, sound, fifth sound and so on. Each step (addition) was discussed by the whole group and if disapproved a different sound had to be chosen. We started discussing with the children the criteria they were using to approve or disapprove a step of the conversation. It became apparent that each added sound had to continue successfully the existing sequence of sounds while at the same time provide something new (some variation). Each added sound had to keep a balance of similarity and change. Through this process the children were discussing and learning about form. As the wind conversation became longer the children felt the need to keep a record of the choices they had made and of the sequence of choices so that they could perform this conversation again. By creating these records they were in essence creating music scores.

kamran's (left) and mima's scores (right)

nigina's score Once the scores were written the children knew, and could memorize, the sequence of sounds. Thus each child could cue the child that was to play the next sound.

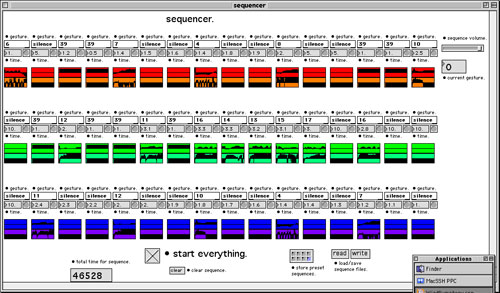

We worked on children cueing each other at the right time so that the very end of each sound could overlap with the beginning of the next one. View this video clip for an example of this process. The children created a conversation lasting approximately 100 seconds. They all like the conversation and all felt that this conversation could become the first part of our performance at the 3rd World Summit. The beginning of our piece was set (You can listen to this conversation by playing back the first 100 seconds or so of the mp3 file of the completed composition). However, we were all getting tired of hearing a conversation of single wind phrases. The children felt that it was time for something different to happen and we talked about that. We decided that the biggest problem was that the conversation was not going somewhere. It was pleasant but after a while it got tiring because it seemed to have no goal. We all agreed that we needed a story, a narrative. How about if we had the conversation slowly turn into a big wind storm? Through this process We asked the children to decide the elements that would have to change to turn a mild wind conversation into a storm. It was agreed that the wind sounds would have to get louder and that we would need to have many wind sounds at the same time during the peak of the storm. We could then have the storm slowly die down by using fewer and softer wind sounds. Through this discussion the children had the opportunity to appreciate the function of a narrative. They learned how to use sound to realise a narrative and they were introduced to some basic procedures and elements of an arch form. They also became familiar with the notions of monophonic texture (the conversation) and polyphonic texture (many winds phrases sounding together to form the peak of the storm) and the different feelings they create. At this point we had to discuss how to address the luck of a large number of independent voices (performers). Since there were only three children, the most phrases that we could have playing together to form the peak of the storm were three. The children agreed that that would not be enough for a big wind storm. For a solution to this problem we introduced children to the notions of automated tasks and multi-tasking. We showed them that through the use of a simple sequencer they could create one layer (one long phrase) of sequential wind sounds and have the computer playback this sequence by itself. This would allow the children to add more sounds, using their Wacom tablets, while the computer was playing the sequence they had already programmed. Please see this video clip for an example of this process. Since now all kids could control two voices we could have up to six voices playing together at the peak of the storm. So the arch form of the storm could be realised successfully. The kids already had many wind sounds in their libraries. The next step for creating our storm was for each child to load some of these sounds in the sequencer in such a way as to create an arch form with the peak of the arch representing the peak of the storm. The children started experimenting with their sequencers and they quickly realised that in order to create this arch form storm they had to place the loudest sounds they had at the peak of the arch. However, each child was still only programming a monophonic sequence. Trough experimentation the children also realised that, when working with a monophonic line, the only way to increase the density of phrases at the peak of the arch, was to enter long silences between the wind phrases at the edges of the arch and have those silences get shorter as the phrase approached its peak. In order to have the three arch form phrases of the three children coincide we agreed that the complete length of their arch would be two minutes. By this point in the process the children were becoming familiar with fairly complex, universal concepts. For example, they were now able to control density and volume of material over time in order to create and arch form.

Mima's storm sequence When all three children had completed their storm sequences we asked them to play back the three sequences together. We wanted to discuss how each child could listen to the three phrases playing together and decide to make changes to his/hers phrase that would enhance the rising and falling storm effect of the combined three phrases. This would give the children a taste of the issues involved in successful polyphony. However, we run out of time. The performance was approaching rapidly and we thus chose to skip this part and move directly to adding more voices. While the three sequences were playing back we asked the children to use their Wacom tablets to add wind sounds that wound enhance the feeling of a rising and then falling storm. After a few takes the children had learned to successfully improvise additional sounds/gestures over the playback of the three storm sequences. The storm part starts at approximately 90 seconds into the composition. After having played their last sound of the wind conversation each child cues their sequencer and the storm begins to build. There is even a small bridge section that connects the end of the wind conversation to the start of the wind storm. During this bridge section the individual sounds of the conversation start overlapping thus creating a smooth passing to the polyphonic wind storm section. The small bridge section was conducted by a member of the staff of the project. The cues given by the conductor/staff member were improvised so that the children would also get a chance to react to unexpected cues. The performance at the 3rd World Summit was accompanied by a video of computer generated graphics. The video screen is split into three. The graphics of each partition are controlled by/map aspects of the sounds created by the computer of one of the children. The video shows in an alternative manner some of the physical aspects of each sound/gesture. The folds of the white graph map velocity and the fragmentation of the background maps the speed of the Wacom pen. Lookat this example video clip. |